Ongoing personal projects

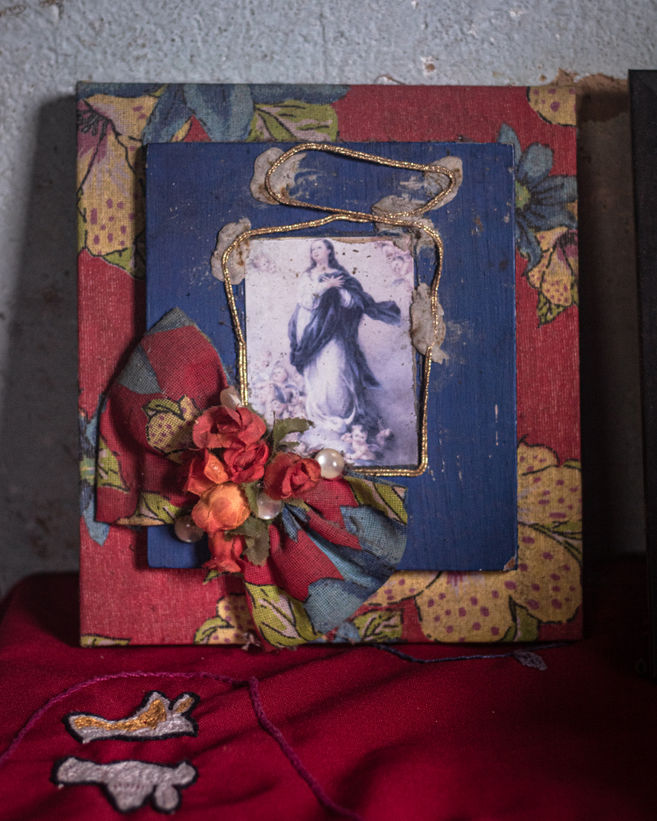

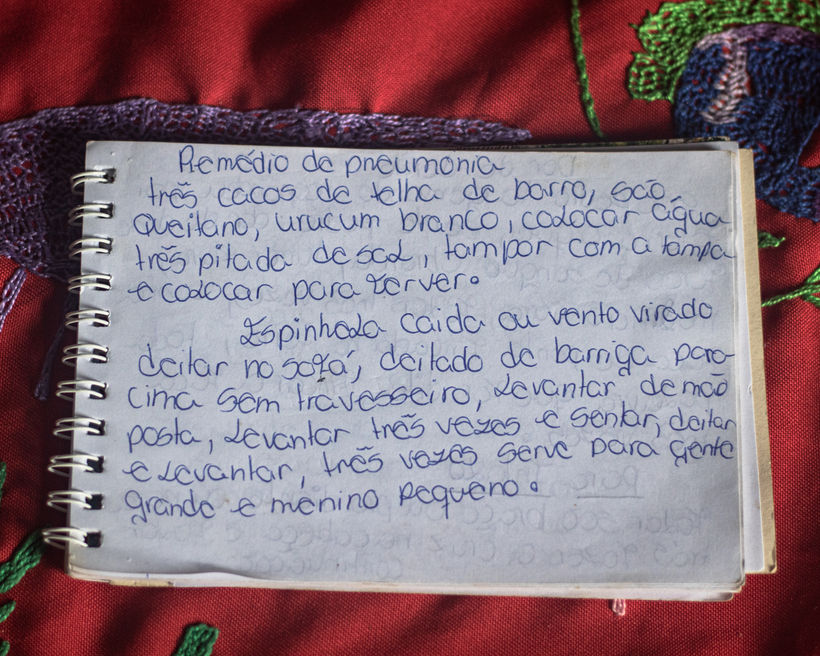

Benzedeiras – women who heal

(Brazil, 2022 - Ongoing) In the Jequitinhonha Valley, in the Brazilian countryside, faith, superstition and reality wander together. Centuries-old syncretic rituals that combine Catholicism with African and Indigenous beliefs converge in the practices of the benzedeiras, women with the God-given gift of healing. From “the evil eye” to diseases such as erysipelas and shingles, benzedeiras know the plants and prayers to cure a myriad of physical and spiritual evils. And each one of them has her own unique rituals. An important element of the Brazilian cultural and religious formation, the tradition of benzer, dates back to the colonial era and has been transmitted orally across generations. Since the year 2000, the craft of the benzedeiras has been nationally recognised as an intangible cultural heritage. Nonetheless, there are no records of how many remain active nor any documentation of their many prayers and rituals. Meanwhile, they are on the verge of disappearing. For benzedeiras, it is a challenge to pass on their knowledge. Most of them live in low income and underserved communities, where there is a growing presence of neopentecostal religions, who condemn the craft as sinful. Besides, new generations, now more urban than ever, are not interested in learning the tradition. As benzedeiras age and pass on, their knowledge fades with them.

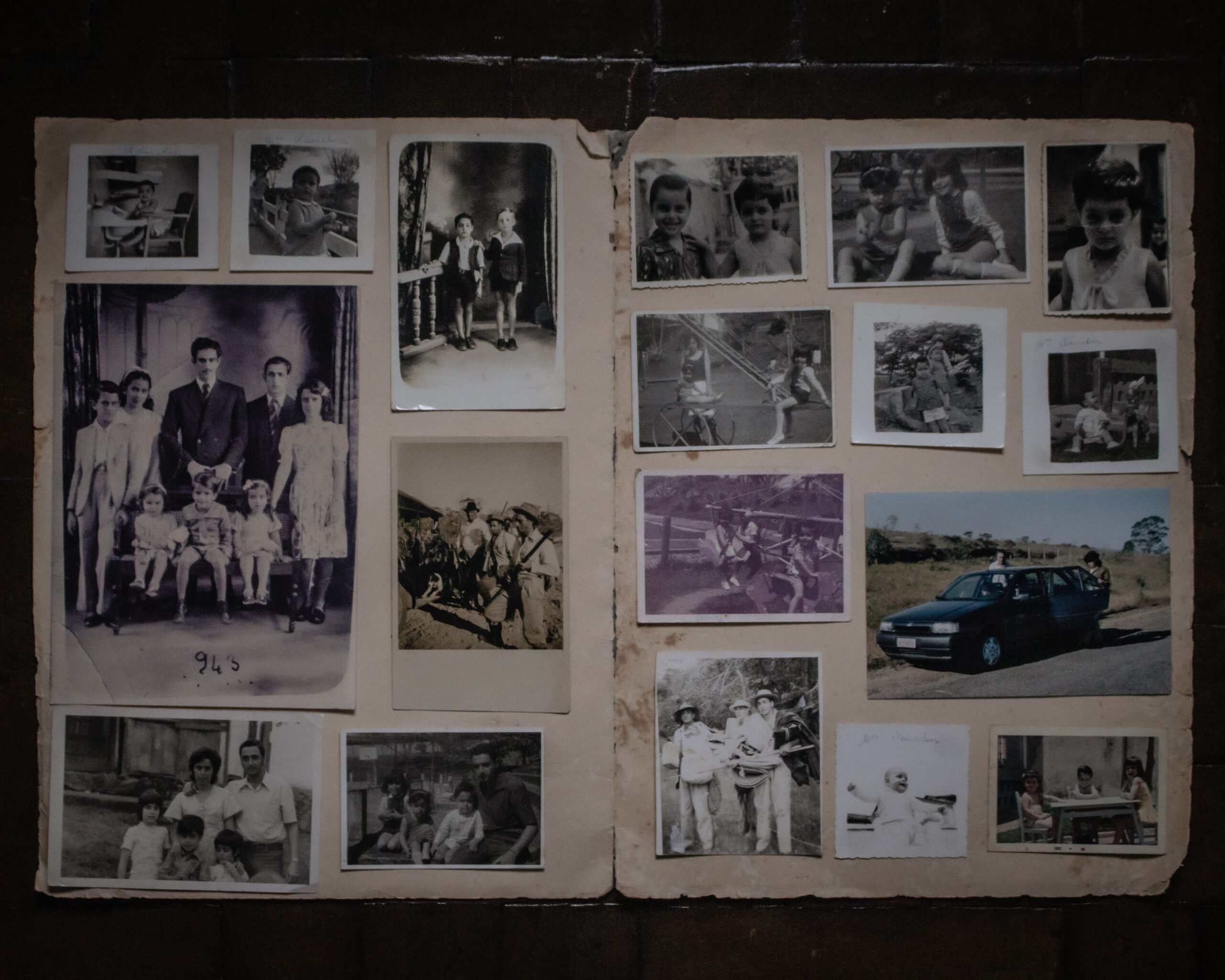

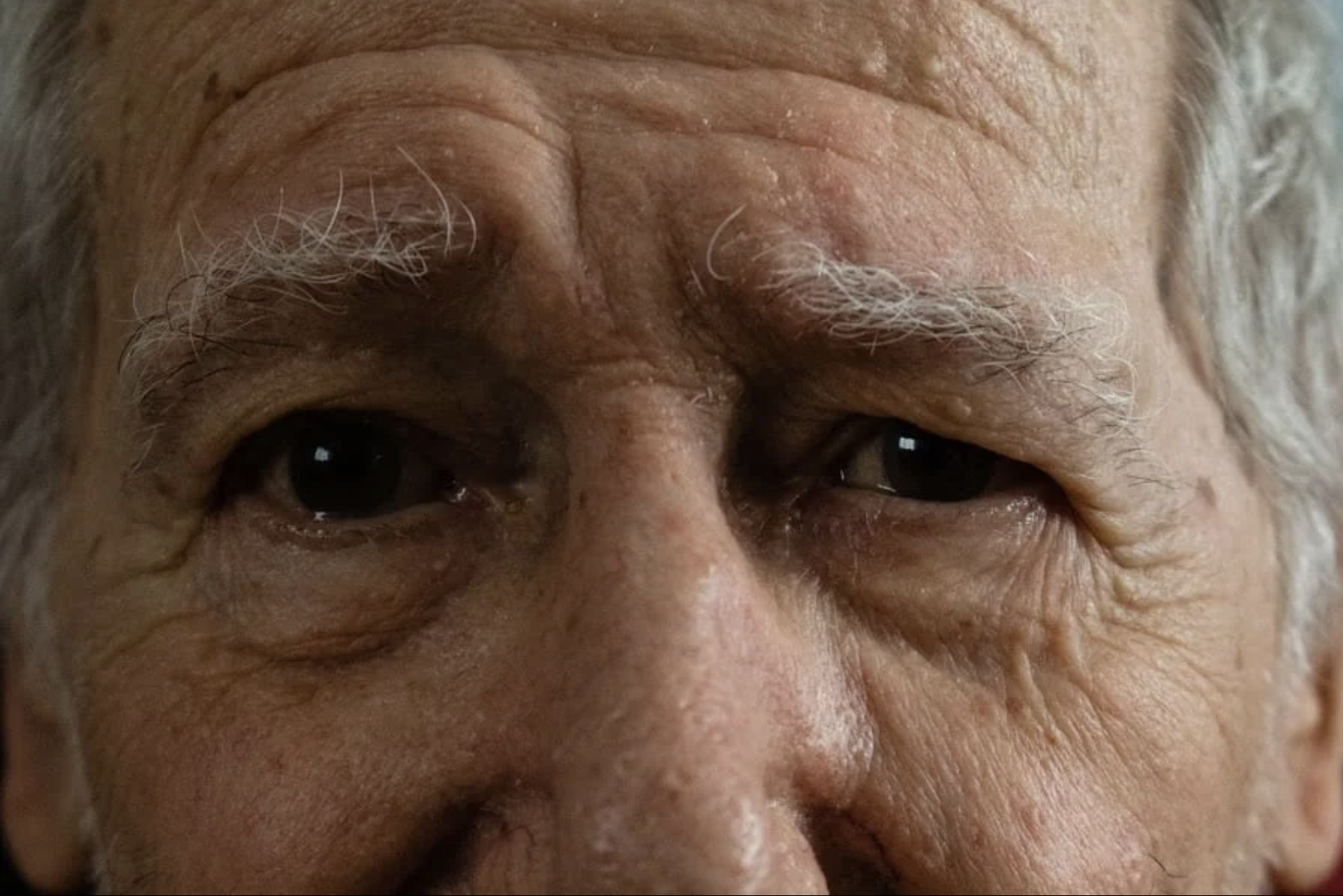

Alinhavo

(Brazil, 2019 - Ongoing) Alinhavo, basting in English, is a sewing technique used to temporarily hold layers of fabric together. As time goes by and loved ones move one, basting is the only way to keep memories and family history more or less in place. Alivanho is not a definite sew. It is but part of an ongoing process, always that one step before the needle and thread take their final turn. Alinhavo is a project I started right before I moved out of Brazil in January 2020, to try to cope with feelings I’m unable to express with words, and to try to hold on to my family, my ancestrality and my heritage. It is a way to document my own personal history and to better understand who I am and where I come from.

In the media

Seeds for a sustainable future

(Roraima, Brasil, 2023) Despite the centrality of the environmental agenda in the new government, saving Amazonia will be no easy task. And this process, complex and multidimensional, begins by getting to know the initiatives already underway and learning from their possibilities and limitations. From agricultural production in community gardens and the circular economy generated by them, to the traditional seed bank with an increasing involvement of Indigenous youth, Serra da Lua shows the way to save the Amazon. The second-largest Indigenous community in the state with a population of almost 10,000, mostly of the Wapichana and Macuxi ethnic group, the region is made up of 32 communities divided into nine Indigenous Territories. Faced with a world that yearns for environmental solutions, this project will document the complexity of this struggle, focusing on the solutions it produces and the lessons to be learned, by Brazil and the world, to save the Amazon and halt climate change. This project received the Dom Phillips Reporting Grant from the Pulitzer Center’s Amazon Rainforest Journalism Fund.

Across the border

(Roraima, Brasil, 2022) By 2022, over 7 million Venezuelans had fled their country, escaping hunger, poverty and political oppression – the biggest humanitarian crisis in the Americas. Over 365 thousand lived in Brazil. Roughly 312 thousand had already received their residence permits and 48,9 thousand had been recognized as refugees. Since 2018, Operação Acolhida, a partnership between the Brazilian government, UN agencies and local NGOs, has concentrated the Brazilian response to this migration. In the state of Roraima, where 75,6 thousand Venezuelans live, Acolhida has eight migrant camps and two transit lodgings that shelter around 7,5 thousand people. But while the country has been internationally praised for its welcome of Venezuelans, the militarization of the humanitarian response and the lack of long-term public policies have been working against the full inclusion of those who arrive. According to IOM’s reports, a population of roughly 3.850 people live in the streets and spontaneous occupations and settlements in Boa Vista, capital of Roraima, and Pacaraima, at the border with Venezuela. The conditions of these settlements are poor. As the land is irregularly occupated, residents are not allowed access to piped water, sewage and electricity. Yet, many choose not to be a part of Operação Acolhida, for different reasons, such as the allegations of mistreatment inside the camps, which include threats, intimidation and even physical assault. Across the border is a project that documents the life of Venezuelan migrants in Boa Vista, both inside and outside of Operação Acolhida.

First stop to safety

(Slovakia, 2022) In Vyšné Nemecké, at the Slovakian border with Ukraine, those who cross the border are welcomed by a wide range of smiley volunteers, who offer from legal information and transport arrangements to food, clothing and shelter. Slovakia is currently the 5th country with the highest number of Ukrainian refugees, having welcomed almost 280 thousand, according to the UNHCR - the biggest migration to the country since the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia. The coordinated efforts of local and international organisations, such as the Red Cross, People in Need, Scouts and Malteser Aid Slovakia, with the support of the local government, have resulted in a camp area with a very organised infrastructure: a complex of volunteer tents, heated sleeping shelters, healthcare teams, a children area and flushing toilets. This project documents the reality of Ukrainian refugees who arrive at this border, in the time they spend between fleeing their country and moving towards their final destination.

Confined Away

(Dublin, Ireland, 2020) Quarantine caught me in a weird place. On March 27th 2020, less than two months after I migrated to Ireland, the whole country was placed under full lockdown. For weeks, two kilometres was the maximum radius within which I was allowed to travel – an infinitesimal fraction of the more than 8.000 km separating Dublin from Belo Horizonte, my home town in Brazil. If you’re a human being on Earth in 2021, you’ve probably experienced some kind of confinement or restriction of movement due to Covid-19 over the past year. And if you’re not incarcerated or a refugee, I’m guessing your experience probably didn’t involve being in an unfamiliar place, lockeddown with people you didn’t know beforehand. I’m guessing you were, at least to some extent, home. I wasn’t. Nor were Beatriz, Alan, Eduardo, Everton, Jonathan, Diane, Pedro, Carla, Felipe and Jéssica – my housemates at 177, Clonliffe Road, Dublin 03. Eleven strangers spread across five bedrooms. Ten Brazilians and one Guatemalan, all but one newly arrived immigrants, who had had no previous contact with one another before setting foot on that house – and before being confined together. It felt like we were the subjects of a social experiment – except there was no one conducting it. Once Covid-19 came upon us, we were no longer allowed to leave for anything other than going to the supermarket. Suddenly, the place I only expected to go back to for eating, showering and sleeping, became my cloister. The sole table in the house, used for eating, studying and working, was never empty – and never silent. Except for a few lucky days, we had to wait in line for cooking and taking a shower; and, in some very unlucky ones, we might even have to wait in line for using the toilet. It was a hard couple of months. During this time, I started photographing everyday life at 177 Clonliffe Road, to try and make sense of my experience. But as the weeks of confinement went by, we went from sharing a house to living together. On Easter morning, Eduardo and Everton got chocolates for everyone in the house. For birthdays, we would get a cake and a card, signed by “your Irish-Brazilian family”. When June finally came, we didn’t skip the traditional Festa Junina: we improvised on costumes and decoration, but the typical food was there. And on almost every Sunday we would have lunch together, like any other ordinary Brazilian family. Although most of us have left 177, Clonliffe Road, we do our best to stay in touch. And as we recollect our time together, the shared memories, the ones we kept, are those of mutual respect and support.

Other projects

Casa, Apartamento, Sobrado - BARRACO

(Diamantina, Brasil, 2023) Casa, Apartamento, Sobrado – BARRACO is a multimedia exhibition that combines installation and photojournalism to bring Ocupação Vitória – a spontaneous settlement in the periphery – to the center of Diamantina. The occupation has existed for years but has grown exponentially during the pandemic when residents of the city and nearby towns and villages found themselves without livelihood alternatives. The idea for the exhibition came to be at a coffee table with Márcia Melo (National Coordinator of the MTST), Helga Espigão (professor at UFVJM) and me, sparked by a question asked by Márcia Melo about the erasure of Barracos (shacks/sheds) in the public sphere. Why do digital platforms, when requesting an address, only offer the options house, apartment or townhouse? What is the difference, if any, between these forms of inhabiting? What is the meaning of a Barraco for people who experience the reality of a settlement? After a meeting with the local Attorney General's Office and Ocupação Vitória, we felt the need for an action that would bring the periphery to the center, where the decisions that define the lives of the 150 families who live at the settlement are taken. Decisions that permeate a fundamental right of any Brazilian person: dignity to live. In the exhibition, my photographs are accompanied by sounds of the settlement (which can be heard through QR codes), by posters where residents answer the question posed by Helga Espigão: “if your shack could talk, what would it say?”, and by a canvas shack built by residents from Ocupação Vitória to mirror the reality of the occupation.

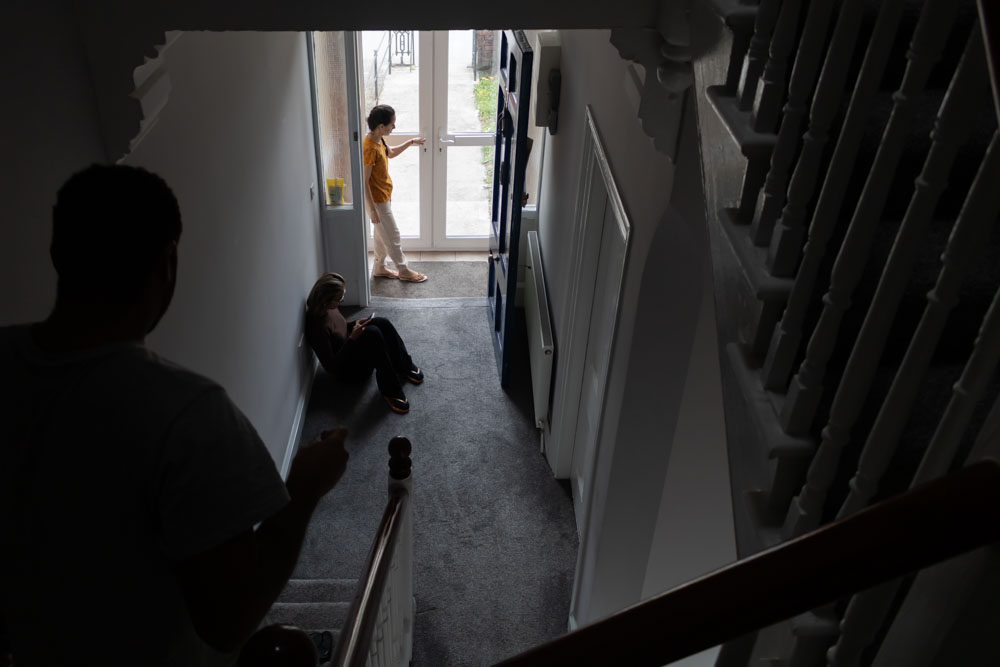

Unbroken

(Denmark, 2021) In March 2021, Denmark became the first country to declare the Damascus area in Syria safe enough for refugees to be sent back. Since then, many people are having their visas reviewed and denied, risking deportation—which, since the country has no diplomatic relations with the Assad government, means being sent to a deportation camp indefinitely. For many families, that means uncertainty and the fear of separation. I had the chance to document three Syrian families as they went through this.